*Published and peer-reviewed article available at DOI: 10.21428/f1f23564.3d7610e0

With nearly 3 billion gamers worldwide, online games and streaming have become a pivotal part of everyday life for people across the globe, leading to new conceptions and constructions of identity, virtually (Hruska). While games have transcended national boundaries, gender, social class, and age, Iranian video games seek to reinvigorate national narratives while simultaneously decolonizing popular culture. However, narratives of Iran from Western-made games often reproduce colonial and imperial agendas. For the purposes of this paper, I will illustrate how Iranian and Western game developers have produced games as a gradual yet perceptible evocation of a perceived Iranian culture. This paper foregrounds the Digital Iran collaborative digital humanities project, a multiplatform online research endeavour across Omeka Classic, WordPress, YouTube, and Twitch. I aim to cast light on video games that attempt to define culture and identity through reimagining historical events, which are then either contested or even glorified by consumers.

In this paper, I first trace the contours of the project, explain the methodological and theoretical frameworks, and provide a rationale for the project’s current iteration. Then, I navigate the dominant narratives of Iran’s modernization in video games by showing the paradoxes and tensions in Iranian video game media through historicizing the Islamic Republic of Iran’s international relations and relations with its own citizens. Rather than merely dichotomizing Western versus Iranian video games, I seek to elucidate how these video games can produce discourse, a discussion and argumentation of ideas and opinions that become instituted as a Western narrative of Iran. To accomplish this task, I perform a close reading of video games through the lens of power. Thereafter, I specify how these dynamics are unique to Iran’s recent history through the expansion of information, communications, and internet technologies and discuss how video games touch on immaterial and material constructs, or rather, the virtual and the real. Through these methods and analyses, my purpose is to imagine new ways of building digital humanities projects with digital tools and platforms that tend to be relegated to popular culture.

Developing Digital Iran, a multiplatform project, requires the expression of concrete historical and cultural elements while exploring ways in which digital games impact the player. Through audiovisual analysis of game aesthetics and affect, Digital Iran examines narratives and counter-narratives of Iranian culture and identity in video games. In many ways, the project materialized organically through independent curiosity, collaborative idea generation, and the linking of theoretical frameworks of power and discourse throughout the span of four years. By focusing on power and discourse, these theories reveal relationships between Western and Iranian societies that are expressed through mundane and extraordinary practices. I bridge the lacuna between discourses of power and the concept of quiet encroachment to produce a nuanced view of international relations and hegemonic goals present within the video game entertainment industry. As a digital humanist, I understand perceptions of Iranian culture through video games using methodological frameworks of close reading, multimodality, and open publication. Through these methods, Digital Iran is imagined through interactions and observations across online spaces. Additionally, my project contributes to the field of digital humanities by showing how some games generate and communicate cultural meaning for purposes other than just gameplay. While looking at a large collection of Iranian and Western video games, my long-term project investigates video games across time through various perspectives, historical patterns, and ethnographic storytelling.

My first goal in this paper is to show how games themselves are part of the mundane and the everyday that are virtual tools for moments of joy, sadness, empathy, resistance, and even repression. Video games facilitate communication through audiovisual aesthetics and narratives that create affectfor the player. When a player experiences affect, either through an interaction or within societal/structural frameworks outside of themselves, it corresponds to an intensity within the body which manifests firstly as a sensation then as an emotion (Shouse). Game development teams sometimes even write game narratives to explicitly cultivate empathy from global gamers, such as Sarkar’s 1979 Revolution: Black Friday (2016). Since games create affect in players, such as empathy or fear, video games and streaming platforms such as Twitch allow players and viewers to expand on these entanglements of embodied experience and affect.undefinedQuiet forms of dissent and discourse are produced in real time through chat interfaces, invoking quiet encroachment among gamers against soft warenacted by a nation state in the form of a game narrative (Bayat 48). Meanwhile, some empathetic games are a response to the Western game industry’s attempt to undermine the Islamic Republic of Iran, while also enactingsoft war in the form of state censorship. While the Iranian state describes soft war (jang-e narm)as a “movement of foreign ideas, culture, and influence into Iran through communications technology,” the state has enacted soft warthrough curtailing and creating cultural products in the communication and technology sectors (Blout 33; Akhavan 5). I define soft waras engendering a cultural impetus and desire to contain a nation-state’s identity or even change that identity from within by either state or citizen actors. While not the primary focus of this paper, I examine the role of social media and technology in the Islamic Republic of Iran, with a brief explanation of the valence of popular protest and politics in entertainment media such as Twitter (Mottahedeh). Through reframing digital humanities as an embodied online experience, Digital Iran uses Twitch and YouTube platforms to portray “immersion, performance, and interactive narrative” in a “new wave” of cultural preservation (Kenderdine 23).

My second goal for this paper is to show how cultural narratives and policies of the state often to correspond and result in citizen resistance to game narratives, invoking quiet encroachment and soft power. Quiet encroachment, unlike protest movements, situates the politics of ordinary life as “noncollective but prolonged direct actions of dispersed individuals and families to acquire basic necessities” such as using public spaces, pursuing informal work, or even engaging in practices of everyday life in the real and the virtual (Bayat 35). Quiet encroachment is about how ordinary people push up against systems of oppressions through non collective action. It is quiet because it nearly goes unnoticed. This type of resistance goes unnoticed because it has very little political meaning or motive attached to it. It is conscious everyday action/doing. When threats to gain becomes more conscious, this is what leads to collective action. Meanwhile, soft power relates to social and political communication, the building of trust, and foreign policy. Soft power is enacted by structures and individuals, whereas hard power is basically coercive military/police state-sanctioned violence, international sanctions, and economic oppression. Those who engage in making games based on soft power seek to acquire a preferred outcome in material and non-material ways so that they may overcome coercive soft war. Quiet encroachmentthereforeleads to the enactment of soft power. The Digital Iran project seeks to substantiate these theoretical underpinnings by showing how video games make arguments about Iranian culture that are then contested or supported by players in and outside of Iran.

What is the Digital Iran Project?

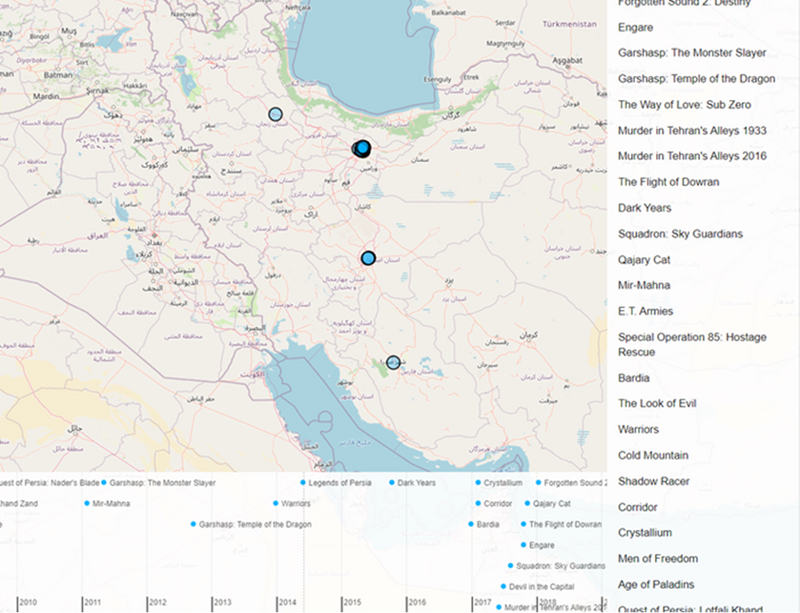

While I initially envisioned a digital humanities project that touched on historical inaccuracies in depictions of the Middle East in video games, I began the Digital Iran project as a curated catalogue of Iranian video games in Omeka Classic for a metadata course at the University of Washington. I was particularly amazed that Wikipedia listed only seven Iranian video games due to the myriad of popular news sources that stated there were many more. The game industry expanded in Iran through publications in the sector of science and technology in 1963, which led to the manufacturing and release of TV Game in 1978, Atari, and eventually the evolution of computers and games culminating in an Iranian video game industry (Hackimi et al.). Meanwhile, US economic sanctions, which include embargoes on trade and imports, have created roadblocks in Iran’s video game industry by blocking access to Google tools, GitHub, and other top-tier software for producing competitive games in the global market (Garst). Studies and popular news sources on Iranian video games are currently limited to the written word, but because games are multimedia texts, fully comprehending a game’s narrative and making compelling arguments about it necessitates the preservation of games digitally, which uncovers deeper semiotic meaning. The original Omeka site, The Digital Borderlands: Glocalizing Iranian Video Games, shows the exact geotemporal spread of games in Iran using the Neatline plugin and uses a multimodal approach to offer a counter-argument to the inaccuracy of Wikipedia. In order to show the pertinence of Iranian games within the global industry, the initial phase of the project includes brief descriptions of each game’s narrative, an image of the game, and the geolocation on a timeline noting when and where each game was produced. The Digital Borderlands project also incorporates explanations of its methodology, US sanctions against Iran, a brief history of the Iranian game industry, gamers in Iran, and a separate section on gender and gaming in Iran. Omeka uses a Dublin Core metadata schema, which is not aligned with current video game metadata practices. For this reason, I catalogued the metadata using the Information School’s “Video Game Metadata Schema” (VGMS) (GAMER Group). However, I found that adapting the VGMS metadata schema and Dublin Core inherently incompatible, so I decided to input pertinent metadata in Omeka and use its tagging feature for what is termed “themes” in the VGMS. Because the Omeka site is an ongoing project, I seek to expand and provide more metadata for each game, continue cataloguing, and incorporate an explanation of the choices I made using a controlled vocabulary while cataloguing the metadata.

By providing a visual model of how Iranian games create discourse with the global game industry, the Omeka site shows that the discourses present in Iranian video games function as counter-narratives to Western-made games. For example, the first-person shooter Special Operation 85: Hostage Rescue (2007), emphasizes the theme Sacred Defense (defa-e moqqaddas), a rhetoric in Iranian culture usually used in defense of the Iran–Iraq war and is commemorated yearly. In this instance, the theme refers to “an ideological struggle with the US” (Šisler 177). Over time, I found using exact geotemporal information to be deeply problematic because it gave the location of Iranian game companies. While my initial rationale felt innocuous, I realized that information such as this could be used for motives beyond the confines of research. To obfuscate the geodata, I simply noted the city the games were created in, which preserved the original intention of the site without exposing game companies to transnational retaliation (Figure 1). To explore video games as digital spaces that afford cross-cultural communication, the next stage in this digital humanities project mustelucidate how narratives and counter-narratives about Iran, Iranian society and culture, and Iranian identities are imagined by different nation states within video games. Although the Omeka site is still a part of the Digital Iran project, I collaborated with others to envision the future of the project beyond cataloguing the dynamics of Iranian and Western made games. To show which games were created to inscribe a particular narrative about Iran, the collaborators and I decided that this initiative needed a visual and aural way of portraying how video games made in different countries produce narratives that conflict with one another.

Beginning in summer 2020, I led a team at the University of Washington that included Solmaz Shakerifard, a Near and Middle Eastern Studies PhD student, and Kayla van Kooten, an undergraduate research assistant, to investigate colonial and anti-colonial representations of Iran in video games. Funded by the Simpson Center for the Humanities and the National Endowment for the Humanities, the Digital Iran project examines video game narratives and shows that, promoted by the market, and at times curated by state agents, the narratives developed by game creators carefully articulate self and the “Other” (Said). Our research team uses discourse analysis of video games’ audiovisual material to convey the complex relationship between games and nation-states. We had proposed to create video essays together so that we could show ways that games presented counter-narratives (e.g., 1979 Revolution: Black Friday), nation-state narratives (e.g., Battlefield 3, Flight of Dowran,and Garshasp: the Monster Slayer), and orientalism (e.g., the Prince of Persia game series). Video essays on the project’s WordPress site show narratives, counter-narratives, and pivotal moments in games while also illustrating an argument. We planned to generate these essays together after we had played each game and discussed our findings in meetings so that we could advance our arguments by annotating game content efficiently and provide effective analysis. Due to COVID-19, however, we could not meet in person. Instead, we streamed on Twitch so that all collaborators could see each game and analyze in real-time their narratives, affect, and aesthetics. Streaming live content allowed transnational observers to contribute their own perspectives and provide nuance we would have potentially overlooked. When van Kooten and I livestreamed on Twitch, for example, we simulated how gamers feel playing a game as they interact with the transnational community of viewers who watch the streams. In some cases, we were impacted mentally and physically by game content because of our own positionalities: our life experiences and social and political contexts related to our identities. For instance, while I played Battlefield 3, I felt an intense inclination to join the fight and regale in the activities. I wanted to make sure objectives were completed and that I enacted all proper protocols. This is on the base semi-conscious level where I felt these emotions. However, I was bothered by my incessant need to complete objectives in the game and my overall dislike of first-person shooter games like Battlefield 3. The reality of staring in the eyes of a military person felt like the snuffing out of life. It is disturbing, if not thought prudently. Shakerifard did not play the game but had a difficult time even watching the game because of her experience growing up during the Iran-Iraq war.

The Digital Iran blog is the academic portion of the project. It currently has posts about Battlefield 3; Prince of Persia: The Sands of Time; and 1979 Revolution: Black Friday. Shakerifard’s post on 1979 Revolution touches on the revolutionary factions and identity during the 1979 Iranian revolution. The Iranian Revolution culminated in a series of events among different leftist and religious groups to dismantle the Pahlavi dynasty and remove the US government–backed Shah. I argue that this game builds empathy in the gamer by sharing photos and recorded content from the revolution. By putting the player in the shoes of Iranians, 1979 Revolution allows them to experience anxiety, hope, and outrage through a historically reimagined moment in time. The 1979 revolution is often associated with Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini, a member of a group of several Iranian politicians, Islamic scholars, and clerical activists who became the first Supreme Leader of the Islamic Republic of Iran. The creators of 1979 Revolution challenge players to unlearn the preconceived notion that the revolution was monolithic by creating moments for players to make decisions to align with either hardlined or liberal communities during the revolution.

In the blog post “Battlefield 3: The Affective Dimensions of Virtual Middle East,” I detail how the game affects my senses and how, through such effects, the game habituates the player to war, leading them to be deadened to violence. This analysis relies on affect theorists Karen Barad (2007), Kathleen Stewart (2007), Ruth Leys (2011), and Lauren Berlant (2011, 2019). In general, the game is deeply problematic because it misrepresents Iraq and Iran. When beginning in the Iraqi Kurdistan zone, for instance, the player sees signs in poorly translated and transliterated Persian, rather than in Arabic or Kurdish (Figure 2). The spectacle of the game situates the player in precarious environments wherein ramshackle Middle Eastern buildings lie in ruins. When playing as Staff Sergeant Henry Blackburn, the game’s US protagonist, the player’s ears are filled with Johnny Cash’s “God’s Gonna Cut You Down” (2003), and they must pass by men who may or may not be part of the fictional faction People’s Liberation and Resistance (PLR), which started a war in the region in 2014. This fictional future inflicted by the PLR, a paramilitary group led by an Iranian named Faruk Al-Bashir, presents the player with a flattened, contrived, and amalgamated vision of the Middle East. Suturing together the fictions and histories that are present within games such as Battlefield 3 and 1979 Revolution as we do in Digital Iran elucidates how soft war and soft power can re-inscribe nation-state narratives while simultaneously invoking discourses produced between nation-states. Battlefield 3, in one extreme, attempts to reify American exceptionalism within gamers’ consciousness, whereas 1979 Revolution situates the complexity of history within terms of empathy to change current perceptions of Iran. Neither of these games are made in Iran, but 1979 Revolution is produced in Iran proper. As might be inferred, positionalities and communities of knowledge influence a game’s narrative.

Figure 2: An edited version of the first 45 seconds of “Operations Swordbreaker,” the second mission in Battlefield 3. The US Marines have just landed in Iraqi-Kurdistan and player sees signs in poorly translated and transliterated Persian, rather than in Arabic or Kurdish (Cohoon).

The Digital Iran team critically examines how games create moments of feeling, affect, and embodiment for us as players, while attending to the historical and ethnographic story-telling portions of the games we survey. Prior to providing an analysis of the Western-made game Battlefield 3 and the Iranian diaspora-made game 1979 Revolution, I will explicate the history of games, gaming, and social media in Iran. In addition to discussing how and why discourse occurs within popular culture entertainment industry, I also illustrate the complexities of the game industry in Iran and the international policy and politics that have led Iranian citizens to obtain bootlegs or other workarounds to accessing games from the West.

A History of Games, Sanctions, and Social Media in Iran

While games arguably stimulate complex emotions, game narratives are curated and therefore produce discourse by the industry through entanglements of information, communications, and internet technology histories. The Iranian game industry drew on prior expertise and knowledge from information technology companies gained over the years with the goal of maintaining Iranian culture (Ahmadi). In its nascent stage, game development concerned itself with edutainment. But over the course of decades, games in Iran became more sophisticated and diverse. Today, Iranian games touch on themes of aliens, the military, Sacred Defense, literature, poetry, and even music. While some scholars question whether Iranian games and gamers can have their own culture because they rely on the same game mechanics as American media, the development of games from the 1980s onward suggests a high level of involvement and concern with conveying Iranian culture in video game content (Šisler).

As a result of the political charge created by the 1979 revolution, the Iranian game industry has treated video games as a sensitive topic and political leaders have declared the dangers of Western cultural attacks via virtual space (Malekifar and Omidi 173). The cultural policy of the new Iranian state aimed to produce a “dignified, indigenous and authentic Islamic culture” (Sreberny and Khiabany 24), and monitoring video games and instituting social policy falls under the Iranian government’s initiative of Sacred Defense. Although the Iranian game industry was not extensive until the 1990s and 2000s, the popularity of games in Iran grew during the Iran–Iraq war, with the first generation of game consoles such as the Atari VCS 2600 (Ahmadi 271). Under Kanoon, a semi-governmental game development company, games were produced with a focus on culture, education, and simplicity. Establishing semi-governmental game agencies became the norm in Iran.

In 2007, the Iran Computer and Video Games Foundation (IRCG) was founded, with the intent of better understanding the broader game industry and to set higher standards within a given game based on whether it follows the soft war agenda. But semi-governmental companies are guided by the Ministry of Culture and Islamic Guidance, which actively selects which games are or are not appropriate for the Iranian consumer. The Center for Development of Information and Digital Media, a subsidiary of the Ministry, oversees festivals that introduce digital media and market of video games, while the Department of Audio-Visual Cooperation, another Ministry subsidiary, issues licenses for games and game developers (Malekifar and Omidi 178). Since there are several governmental agencies responsible for video game production and distribution in Iran, the Iranian government’s National Plan for Computer Games in Iran, guided by the High Council for Cyberspace, supervises and regulates game production to boost the game industry in Iran (IRCG 11).

By close reading games and engaging with media history, the Digital Iran project uncovers how video games relate to social, political, and cultural reconfiguration through censorship and protest (Zayani 3). Like the game industry, other media is heavily regulated in Iran. Yet, in Iran and the Middle East more broadly, media and internet culture has led to galvanization of the masses against their respective government’s injustices, which in recent history manifested as the 2009 Iranian Green Revolution, the Arab Spring, and Turkey’s Gezi Park protests. Scholars often argue that the role of social media in the Middle East and protest occurs only when there is a weakened central authority (Khiabany 224). During the 2009 Iranian Green Revolution, for example, the Iranian government viewed social media as a tool that was being used to undermine the cultural values of the Islamic Republic and simultaneously used social media as a space for soft war tactics to squash opinions that undermined them (Akhavan 5). The Iranian government censorship strategy consists of spreading disinformation so that their strategic control of information can “manipulate public opinion, garner support, and discredit opponents” as well as “curb ‘dissenting’ speech and behavior” (Kargar and Rauchfleisch 1522). As a form of soft war, online control has led to weaponized propaganda and therefore has real-world implications among citizens. For internet and Twitch streaming, for example, Iranian citizens often have difficulty accessing some websites online and therefore use VPNs to skirt internet controls. Meanwhile, streamers access donations from viewers through PayPal as a workaround to US sanctions that prevent direct money exchange.

Despite citizens using such quiet encroachment methods, the Iranian government aims to develop new technology and media through its censorship initiatives. The central state has sought to control expression of this multimedia content, to moderate online participation, and to inhibit any form of protest toward the government that burgeons on online platforms. Social media and gaming are therefore linked through the discursive nature of meme culture, trolling, and GIFs. Twitter is often paired with Twitch because gaming circles can exploit its ability to share things quickly. This pairing is often instigated by game fans and gamers who use social media platforms as a way to garner attention and gain followers on the streaming platform. Like social media censorship in Iran, content control of gaming is therefore a governmental concern. The Iranian government has approximately 30 bureaucratic institutions that regulate the games industry in Iran and therefore prevent anything that could potentially undermine the cultural values of the Islamic Republic (Malekifar and Omidi 178). Because of the Islamic Republic of Iran’s hypervigilance in censoring games, Iranian gamers tend to see Iranian games as a form of propaganda.

Among Iran’s 80 million citizens, approximately 23 million are gamers (IRCG 7). Of these gamers, 37% are women. This interest in gaming can be linked to the internet user population in Iran, which has an 82% penetration rate, which, according to the IRCG, is the biggest in the Middle East (4).undefined The local socio-cultural context among Iranian gamers is further impacted by US sanctions that have, at least on paper, prevented Iranian access to online video games. In addition to Iranian law, US sanctions against Iran (sections 4.3 of Annex II and 17.1 of Annex V of the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action) hinder Iranian access to video games. Iranians also lack access to a public cloud (for example GitHub, Google, and Riot Games), and US foreign policy further bolsters sanctions and maximum pressure policies against Iran, further prohibiting full access to the internet and games such as World of Warcraft (Farnan et al.). Coupled with the fact that Iranian games are deeply censored by the video game industry, maximum pressure policy under the previous US administration has sought to ratchet up economic sanctions upon the Iranian government, which consequently enforces punitive measures that prevent Iranians from accessing digital subscription services and basic communication platforms, such as email, over the internet. Sanctions and maximum pressure policy thus impair the everyday use of internet technologies through “entanglements born of capitalist alienation” including trade and access to the global economy (Osanloo 4). Despite these hurdles, Iranians use VPNs, pre-paid debit cards, and transnational bank accounts to prevent their online isolation from the global online gaming community.

While Iranian gamers purport that access to games is about enjoyment and fun, their aspiration to gaming normativity implicates a political and economic reality debilitated by local and international controls. “Halal internet,” a term for the national telecommunications infrastructure known as the National Information Network, aims to cut reliance on international applications such as Telegram, an instant messaging app (Kargar). The National Information Network houses an “internet-based network with switches, routers, and data centers, so that internal access requests for information stored in internal data center are not routed abroad at all” (Approvals). This refers, in unequivocal terms, to the censorship of internet content and restriction of access to websites, which is deemed by the High Council of Cyberspace as intelligent filtering of the internet to conform to Islamic principles. The censorship has manifested, for instance, as temporarily blocking Telegram and Instagram in January 2018 (Kargar). In addition to centralized equipment, the Iranian internet censorship project relies on a Cyber Police unit known as FATA to “monitor Iranians’ online activities,” which leads to the prosecution of so-called online dissidents (Aryan et al. 1). Iranians find ways to remain connected to the global community and economy, however, despite the attempts of the National Internet Network to hamper access to “undesirable” content.

Discussion

The Digital Iran project uncovers how games induce an affective state and then become embodied through the player. In addition, the project elucidates how games are sites of contention that inscribe, counter-inscribe, and erase systems of power and domination, as well as sites for creating discourse and subjectivity (Burril 26). Battlefield 3 is a prime example of soft war being inscribed in a game, resulting in the invocation of affect within a player. This first-person shooter (FPS) game is set in 2014, during a fictional war that takes place in Tehran and the Iraqi Kurdistan region of Iran. The game places the player in virtual Middle Eastern-like spaces. As mentioned above, for the majority of Battlefield 3,a gamer plays as Sergeant Henry Blackburn of the US Marines 1st Recon Battalion, with the aim of fighting the fictional Iranian paramilitary known as the People’s Liberation and Resistance (PLR). The PLR staged a coup d’état in Iran, leading to the US infiltration. Blackburn, along with other US marines, pursue the PLR main antagonists Faruk Al-Bashir, a former General of the Iranian Air Force, and Solomon, an ex-CIA operative. Among the operations or levels within Battlefield 3, the player—as Blackburn or a Russian paratrooper—must hunt down and recover nukes that the PLR stole from Russia and planned to use in major metropolitan areas in Europe and the US By staging an imagined war, Battlefield 3 works as a form of discursive or subliminal narrativizing of Iran as problematic and led by terrorists, while simultaneously invoking so-called “American greatness” through imagining how a war could transpire in Iran. Players experience the hostage taking and videotaped execution of a Marine by Al-Bashir, which is viewed by Blackburn in the exact place where the event occurred. From the perspective of Blackburn, viewers see a ransacked building with the blood of the Marine pooled on the floor. When I play Battlefield 3, I face and then re-experience the violence that has been perpetrated in the game and yet feel compelled to complete the game’s objectives. An FPS game aims to motivate the player to not only want to become good with the use of virtual artillery but to also successfully achieve the mission’s objectives by terrorizing the virtually imagined Iranian body. I notice how, when playing, my physical body is largely ignored yet my sense of self is extended through the identity of the virtual character I play. Even though the game is fictional, I experience an imagined war predicated on current and past international conflicts between the US and Iran, and the Middle East more broadly. Because reality seeps into the virtual in this game, the game becomes affective labour for me as the player (Ahmed 119). Specifically, I perform affective labour wherein I experience emotional deficits or challenges due to social and/or power relations present in the games content (Anderson 78). By experiencing social and power dynamics in the game that represent Iran and US relations, I am actively participating in a virtual war. While in game, I am required to shoot PLR troops and accomplish other objectives such as aerial targeting. These moments are charged emotionally because I must take action against virtual bodies that represent an actual people. As a result, my virtual presence is moving through these entangled relations and being subjected to soundmedia scapes that intend to invigorate my desire to accomplish an objective. Often, I am rendered with emotions of intensity, and even anxiety.

I am not the only one who experiences Battlefield 3 affectively through the body. For others on the Digital Iran team, Battlefield 3 creates multiple negative affectsthrough visual, reverberating, and aural sensations. Every individual on the research team experienced flowing emotions and feelings of fear while bearing witness to a misleading conception of Iran. While not every player will experience Battlefield 3 the same way, the political landscape of the game, acting through the mechanism ofsoft war, manipulates perceptions and consciousness. Another way to look at the game is merely to think about how the soundscape impacts the body. Digital Iran endeavours to show how certain “sound-media” landscapes in games may oppose or even create affect and impact perceptions (Leys 461). For instance, “Going Hunting,” the fourth campaign in Battlefield 3, engages in soft wartactics through its sound-mediascape as sound becomes internalized by the player, galvanizing them to take part in virtual war, for example through the sounds of a US Navy air strike. As players, our ears are filled with cabin dissonance in the fighter jet along with intensified music as Iranian enemy jets trail behind. We then destroy the Iranian PLR aircrafts to meet the next objective: the Mehrabad Airport. Audiences never see the character that controls the artillery on the jet nor hears their voice. The character’s name is Lieutenant Jennifer Hawkins, a Weapons System Officer, and the only female character in the game. Audiences will never hear or see a female character that they are playing whereas, male voices and masculinized sound-mediascapes are capitalized on.

Battlefield 3 will likely invoke historical memory within a player who is versed in histories of US–Iranian conflicts or has experienced these histories firsthand. During the research team’s live streaming events, Iranian viewers and collaborators noted interlaced history throughout the game, which magnified, compounded, and released deep feelings of discomfort and anxiety. For example, when I siege the virtual streets of Tehran as a US marine with artillery, seeing known landmarks like Milad Tower as bullets rain down on Iranians and US troops, I note that the sound-media landscape creates an internalized experience of being in virtual war, producing anxieties and intellectual turmoil. As students and future scholars in Iranian Studies, the Digital Iran team felt that the game summoned historical and interrelated memories and projected them into our consciousness. My collaborators and I particularly recount the complexities of the Iranian revolution among secular and conservative political groups against a US-supported Shah which led to establishment of the Islamic Republic of Iran. The immediate response to President Jimmy Carter’s decision to welcome the Shah to the US led to the Iranian hostage crisis of 1979 in which, over the course of 444 days, fifty-two American diplomats and citizens were held hostage. US policies with Iran continued to be questionable, including playing off tensions and feeding weapons to both Iran and Iraq during the Iran–Iraq war of 1980–1988 and imposing the current economic sanctions against Iran that impact ordinary citizens. By asking “what if” through an imagined future, Battlefield 3 reinvigorates the idea of an imperial culture of American exceptionalism and Iranians as “Other”: during this fictional war, Americans can save Iranians from themselves. The confusing palimpsest of landmarks and monuments foisted onto a similar yet illusory virtual Iranian landscape with Arabic writing and English graffiti warps perception and corrupts cultural knowledge about Iran.

Like Battlefield 3, Prince of Persia: The Sands of Time captures the sentiment of a flattened and negatively gendered Middle East. To close read the Prince of Persia game series, Battlefield 3, 1979 Revolution, Flight of Dowran, and other Iranian games, I found that the method of streaming gameplay in real time proved to be helpful in disseminating our initial findings and simultaneously gathering opinions from viewers. I particularly delighted in discovering how Twitch’s online structures and modalities provided a crash course on gaming and spectatorship that would not have been experienced by merely watching another streamer. By playing games in real time with spectators, the team could analyze and create discourse rapidly. (Taylor 23). From the othering mechanisms of Persian viziers in Prince of Persia to American exceptionalism in Battlefield 3, the viewers and the Digital Iran research team discussed how forms of soft war and soft power are present in these video game narratives. Through suturing together foreign ideas about Iran, Battlefield 3 is arguably an articulation of a cultural narrative of the West and its perceptions of the “Other” as in need of saving or subordinating through imagined war; Prince of Persia instills a sense of orientalism. Yet, transnational viewers found the game relatable and nostalgic, as they had played it during their childhood.

Figure 3: Prince of Persia Video Essay on Caricatures and Masculinities

As I argue in a blog post entitled “Prince of Persia and Queering the Near East,” Prince of Persia: The Sands of Time unconsciously invokes Islamophobia and queerphobia. While streaming on Twitch in summer 2020, van Kooten and I connected and engaged with the broader gamer and academic community who have played Prince of Persia. Based on the viewers’ sentiments and our embodiment while playing, I would argue that the Prince of Persia provides an amalgam of the Iranian, Arab, and Indian-Hindu culture jumbled together confusedly, provoking an uncomfortable anxiety with the narrative content. In one instance, a viewer pointed out the “unconscious Islamophobia” present throughout the game (Cohoon). Yet, many in the gamer community love Prince of Persia because they relate to the very same identities represented throughout the narrative: Iranian, Muslim, Hindu, and even Pashtun. I learned quickly from the viewers that their own identities richly perplex the game content: there simply cannot be a one-size-fits-all interpretation of it. The viewers grew up enjoying Prince of Persia, and still know the mechanics of these games through their muscle memory. Yet, one graduate student in London, despite deep adoration of Prince of Persia, stated that the developer Jordan Mechner “relied heavily on the Indian-Hindu culture to create the scenery of the game because the archaic Iranian culture has diminished” and that such discourse “implies that contemporary Iran possesses no remnants of archaic Iran” (Cohoon). In addition, queer masculinities are digitized in the Prince of Persia narrative as both inherently weak and ill. This is particularly evident with the evil Vizier, better known as Jaffar in the earlier game called The Prince, based on Disney’s Aladdin (1992) and One Thousand and One Nights (ca. 800). The Vizier seeks to unleash the sands of time, while he wavers in health. The camera pans to the Vizier, and the player watches the character cough blood into a handkerchief, and his face and mannerisms are feminized (Figure 3). Although the character is based on Jaffar ibn Yahya of the Abbasid caliphate, an eighth-century Persian vizier, patron of science, and papermaking enthusiast, the historical figure has been rendered in the modern imagination as a queered and othered villain (Watt).

While Prince of Persia uses well-known literature and capitalizes on our collective memory of Disney’s Aladdin,1979 Revolution relies on interviews, photographs, and stories of Iran’s 1979 revolution, with audiovisuals deeply rooted in the aesthetic culture and representation of Iran. Battlefield 3 misrepresents Iran and distorts the Persian language, whereas 1979 Revolution: Black Friday uses audial and visual Persian to develop resonances of place and space in Iran. By experiencing streaming and independent play, the research team learned how the 1979 Revolution gameprovides a non-material way to overcome coercive soft warin the game industry and/or games like Battlefield 3. Throughout the game, the player experiences a rich palimpsest of sounds and architecture recognizable as 1978–1979 Iran from the perspective of Reza Shirazi. Throughout 19 chapters, the player guides Reza throughout the streets of Tehran, taking part in protests, and becoming familiarized with protest organizations. Despite this decision-making process, Reza is bound to experience the same moments in time, eventually leading to his own imprisonment in 1980. While in Evin Prison, we learn that Reza, a photo journalist, is being interrogated by Asadollah Lajevardi who accuses him of participating in the revolution against Ayatollah Khomeini. Throughout the interrogation, the player then experiences a series of flashbacks. The first flashback is in September 1978, Reza, then 18 years old, hangs out on the rooftop with his friend Babak Azadi thinking about the revolution. Reza is taking photos of street protestors, while discussing the motivation of protest with Babak. Throughout the game the player’s decision-making process may reflect choices that represent pacifism, support of the Iranian Shah and even Reza’s police officer brother Hossein Shirazi, or taking on active role in the revolution. While the player must make choices that change the outcome, they experience several moments that were present during the historical revolution. Particularly, the player hears common mottos and chants including “marg bar shah” (death to the Shah) and “esteqlal, azadi, jomhuri-ye eslami”(independence, freedom, the Islamic Republic), situated in the streets and bazaars of Iran. In many ways, the game acts as a social non-movement or quiet encroachmentbecause it works to discreetly provide varying historical narratives of ordinary people, engage with past social movements, and critique dominant positions and perspectives held in Iran and the West. Based on these theoretical framings, I posit that the 1979 Revolution game constitutes soft power.

Through the Digital Iran project, I focused on process and product for digital explorations. I collaborated and reimagined ways in which digital humanities work could be realized by using the popular culture platform Twitch. By utilizing Twitch live streaming and blogging as digital tools for uncovering a game’s audiovisual affect, future digital humanities research can expand on and improve on our work. Curating, cataloguing, engaging with online communities, and critically examining games delivered several data points, from emotions, sentiments of belonging, and even historical information. Recent scholarly examinations of Iranian video games have used text to analyze games or merely provide a timeline of events. Engaging with viewers and colleagues in real time during the COVID crisis provided new possibilities to connect across the internet, meaningfully, through Twitch, that are currently unprecedented in digital humanities research. Additionally, the research team and I re-evaluated the video essay format (traditionally used for cinema) for video games.

While Digital Iran employed new visions of traditional paradigms, the experience of working on a collaborative project led to realizations about knowledge gaps within the academy, particularly regarding essential research skills for video game analysis. I am hoping to bridge this gap in knowledge while continuing my work on Digital Iran. My aim is two-fold. I desire to prepare lessons based on the fields of media, ethnography, and science and technology studies, scaffolded with game content while streaming live on Twitch. Because full videos on Twitch are only saved for up to 60 days if a streamer links their Amazon Prime account and their Twitch account, these videos would then be uploaded to YouTube to create a persistent website link. By creating content that is understandable and educational for academic and non-academic audiences, Digital Iran will have a broad impact. To maximize this impact, my second goal is to begin a podcast and a separate blog that touches on the pedagogical and research practices I have learned throughout the Digital Iran project. Envisioning a dialogue between me and UW students will continue to shape the course of my research, which would not be possible on my own. After all, it is through shared and continued dialogue with collaborators that digital humanities work is most fruitful. To accomplish these goals, I will continue to use Twitch to disseminate findings on Digital Iran as well as my dissertation research findings, and critically examine games as discourse.

Works Cited

1979 Revolution: Black Friday. Microsoft Windows, iNK Stories, 2016.

Ahmadi, Ahmad. “Iran.” Video Games Around the World, edited by Mark J.P. Wolf. MIT Press, 2015, pp. 271–291.

Ahmed, Sara. “Affective Economies.” Social Text 79, vol. 22, no. 2, 2004. Duke University Press, pp. 117–139. doi.org/10.1215/01642472-22-2_79-117.

Akhavan, Niki. Electronic Iran: The Cultural Politics of an Online Evolution. Rutgers University Press, 2013.

Anderson, Ben. “Affective Atmospheres.” Emotion, Space, and Society vol. 2, no. 2, 2009, pp. 77–81. doi.org/10.1016/j.emospa.2009.08.005.

“Annex II- Sanctioned-related Commitments.” US Department of State, 14 July 2015. 2009-2017.state.gov/documents/organization/245320.pdf. Accessed 22 July 2021.

“Annex V- Implementation Plan.” US Department of State, 15 July 2015. 2009-2017.state.gov/documents/organization/245324.pdf. Accessed 22 July 2021.

“Approvals of the 15th Session of the Supreme Council of Cyberspace regarding the Definition Requirements Governing the Realization of the National Information and Budget Network in 2015 of the National Cyberspace Center.” High Council of Cyberspace, no. 20082, 2014. www.rrk.ir/Laws/ShowLaw.aspx?Code=1640. Accessed 1 Mar. 2020.

Aryan, Simurgh, Homa Aryan, and J. Alex Halderman. “Internet Censorship in Iran: A First Look.” FOCI 2013. www.usenix.org/system/files/conference/foci13/foci13-aryan.pdf.

Barad, Karen. Meeting the Universe Halfway: Quantum Physics and the Entanglement of Matter and Meaning. Duke University Press, 2007.

Battlefield 3. Microsoft Windows, DICE, 2011.

Bayat, Asef. Life as Politics: How Ordinary People Change the Middle East. Stanford University Press, 2013

Berlant, Lauren. Cruel Optimism. Duke University Press, 2011.

Berlant, Lauren, and Stewart, Kathleen. The Hundreds. Duke University Press, 2019.

Blout, Emily. “Iran’s Soft War with the West: History, Myth, and Nationalism in the New Communications Age.” SAIS Review of International Affairs vol. 35, no. 2, 2015, pp. 33–44. doi.org/10.1353/sais.2015.0028.

Burrill, Derek A. “Queer Theory, the Body, and Video Games.” Queer Game Studies, edited by Bonnie Ruberg and Adrienne Shaw, University of Minnesota Press, 2017, pp. 25–34. jstor.org/stable/10.5749/j.ctt1mtz7kr.

Cohoon, Melinda. “Battlefield 3: The Affective Dimensions of a Virtual Middle East.” Digital Iran: Anticolonial and Imperial Narratives of Iran in Video Games, edited by Melinda Cohoon, Solmaz Sharkerifard, and Kayla van Kooten, 10 Aug. 2020. digitaliranproject.com/battlefield-3-the-affective-dimensions-of-a-virtual-middle-east/.

———. “Neatline.” The Digital Borderlands: Glocalizing Iranian Video Games. Last updated 06 October 2020. iranianvideogames.com/cms/

———. “Prince of Persia and Queering the Near East.” Digital Iran: Anticolonial and Imperial Narratives of Iran in Video Games, edited by Melinda Cohoon, Solmaz Sharkerifard, and Kayla van Kooten, 15 October 2020. digitaliranproject.com/prince-of-persia-and-queering-the-near-east/.

Cohoon, Melinda, Shakerifard, Solmaz, and van Kooten, Kayla. Digital Iran: Anticolonial and Imperial Narratives of Iran in Video Games. July 2020. digitaliranproject.com/.

Farnan, Oliver, Joss Wright, and Alexander Darer. “Analyzing Censorship Circumvention with VPNs Via DNS Cache Snooping.” IEEE Security and Privacy Workshops (SPW) 2019. doi.org/10.1109/SPW.2019.00046.

Garst, Aron. “Video Game Development in Iran: Limited Tools, Front Companies and a Specter of War.” The Washington Post, 5 Feb. 2020. www.washingtonpost.com/video-games/2020/02/05/video-game-development-iran-limited-tools-front-companies-specter-war/.

GAMER Group. Video Game Metadata Schema Version 4.1 University of Washington Information School. 16 September 2020. cpb-us-e1.wpmucdn.com/sites.uw.edu/dist/2/3760/files/2019/09/VGMS_Version4.1_20201009.pdf.

Hackimi, Arash, Saeed Zafarany, and Brandon Sheffield. “Iran Video Games Timeline: From 1970 to 2019.” Gamasutra, 2 Mar. 2020. www.gamasutra.com/view/news/358953/Iran_video_games_timeline_from_1970_to_2019.php. Accessed 15 Mar. 2021.

Hruska, Joel. “3 Billion People Worldwide are Gamers, and Nearly Half Play on PCs.” Extreme Tech. 19 Aug. 2020. www.extremetech.com/gaming/314009-3-billion-people-worldwide-are-gamers-and-nearly-half-play-on-pcs. Accessed 10 Feb. 2021.

Kargar, Simin. “Iran’s National Information Network: Faster Speeds, but at What Cost?” Internet Monitor, 21 Feb. 2018. www.thenetmonitor.org/bulletins/irans-national-information-network-faster-speeds-but-at-what-cost. Accessed 10 Feb. 2021.

Kargar, Simin and Adrian Rauchfleisch. “State-aligned Trolling in Iran and the Double-Edged Affordances of Instagram.” New Media & Society vol. 21, no. 7, 2019, pp. 1506–1527. doi.org/10.1177/1461444818825133.

Kenderdine, Sarah. “Embodiment, Entanglement, and Immersion in Digital Cultural Heritage.” A New Companion to Digital Humanities, edited by Susan Schreibman, Ray Siemens, and John Unsworth, Wiley/Blackwell, 2016, pp. 22–41.

Khiabany, Gholam. “Citizenship and Cyber Politics in Iran.” The Digital Middle East: nState and Society in the Information Age, edited by Mohamed Zayani, Oxford University Press, 2018, pp/ 217-237.

IRCG (Iran Computer and Video Games Foundation). Iran’s Game Industry: Essential Facts & Key Players. 25 Aug. 2016. en.ircg.ir/news/59/Iran%E2%80%99s-Game-Industry:-Essential-Facts-and-Key-Players-. Accessed 1 Mar. 2020.

“Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action.” US Department of State, 14 July 2015. 2009-2017.state.gov/documents/organization/245317.pdf. Accessed 22 July 2021.

Leys, Ruth. “The Turn to Affect: A Critique.” Critical Inquiry vol. 37, no. 3, 2011, pp. 434–472. doi.org/10.1086/659353.

Malekifar, Siavosh and Mahdi Omidi. “Innovation in the Computer Game Industry in Iran.” The Development of Science and Technology in Iran: Policies and Learning Frameworks, edited by Abdol S. Soofi and Mehdi Goodarzi, Palgrave MacMillan, 2016, pp. 171–187.

Mottahedeh, Negar. #iranelection: Hashtag Solidarity and the Transformation of Online Life. Stanford University Press, 2015.

Osanloo, Arzoo. “Entanglements: Lives Lived Under Sanctions.” Iran Under Sanctions, 2021, pp. 1–32. static1.squarespace.com/static/5f0f5b1018e89f351b8b3ef8/t/6074aa7c815ed607dde6dcd8/1618258557269/IranUnderSanctions_Article11_v2.pdf. Accessed 13 April 2021.

Prince of Persia: The Sands of Time. Microsoft Windows, Ubisoft, 2003.

Said, Edward. Orientalism. Vintage Books, 1978.

Sarkar, Samit. “1979 Revolution Developer Explains How Hard It is to Make Emotional Games: You have to Entertain and Engage Players.” Polygon, 28 June 2016. www.polygon.com/2016/6/28/12025654/emotional-games-empathy-navid-khonsari-games-for-change. Accessed 15 Jan. 2021.

Shakerifard, Solmaz. “1979 Revolution: Black Friday.” Digital Iran: Anticolonial and Imperial Narratives of Iran in Video Games, edited by Melinda Cohoon, Solmaz Sharkerifard, and Kayla van Kooten, 06 Aug. 2020. digitaliranproject.com/1979-revolutionblack-friday/.

Shouse, Eric. “Feeling, Emotion, Affect.” M/C Journal vol. 8, no. 6, 2005, doi.org/10.5204/mcj.2443.

Šisler, Vit. “Video Game Development in the Middle East: Iran, the Arab World, and Beyond.” Gaming Globally: Production, Play and Place, edited by Nina B. Huntemann and Ben Aslinger, Palgrave Macmillan, 2013, pp. 251–272.

Special Operation 85: Hostage Rescue. Microsoft Windows, Association of Islamic Unions of Students, 2007.

Sreberny, Annabelle, and Gholam Khiabany. Blogistan: The Internet and Politics in Iran. I.B. Tauris, 2010.

Stewart, Kathleen. Ordinary Affects. Duke University Press, 2007.

Taylor, T. L. Watch Me Play: Twitch and the Rise of Game Live Streaming. Princeton University Press, 2018. doi.org/10.2307/j.ctvc77jqw.5.

Watt, William Montgomery. “Hārūn al-Rashīd.” Encyclopedia Britannica, 20 Mar. 2021, www.britannica.com/biography/Harun-al-Rashid. Accessed 22 July 2021.

Zayani, Mohamed. “Mapping the Digital Middle East: Trends and Disjunctions.” Digital Middle East: State and Society in The Information Age, edited by Mohamed Zayani, Oxford University Press, 2018, pp. 1–32.

Acknowledgments

I would like to express my sincere gratitude to the institutional donors that funded my research project. With awards, grants, and fellowships from the Walter Chapin Simpson Center for the Humanities, the Roshan Cultural Heritage Institute, Near Eastern Languages and Civilization at University of Washington, and the Social Science Research Council’s Social Data Research and Dissertation Fellowships, I had the tremendous opportunity to experience, think, and collaborate, and express myself on a multiplatform digital humanities project imperative to my doctoral dissertation. I am also deeply grateful to my mentors Professor Arzoo Osanloo, Professor Selim Kuru, and Professor Aria Fani who have supported and guided me during the research process. My friends, viewers, colleagues, and the Digital Iran Research team— especially including the research assistant Kayla van Kooten who jumped into the deep end of Twitch experimental exploration—were indispensable to the Digital Iran project. A special thanks to Jennifer Freeland for supporting the project, as well as reading and editing a draft of this essay. Lastly, I am appreciative of my husband Jeromy Simms who helped moderate and contribute discourse on video games in real-time on Twitch.